This study was published for the first time in 2011 in a book titled: DeArabizing Arabia: Tracing Western Scholarship on the History of the Arabs and Arabic Language and Script (ISBN: 978-0-9849843-0-5)

by Saad D. Abulhab

CHAPTER 3

The al-Namārah Nabataean Arabic Inscription (328 CE)

3.1 Introduction

The inscription of al-Namārah

is by far the most important, controversial, and challenging pre-Islamic Arabic

inscription— it is the earliest discovered but youngest dated inscription of

only three Nabataean inscriptions considered by Western scholars today as fully

Arabic. It is also the oldest Arabic document on record with relatively good

classic Arabic language. Dated 328 AD and written in clear cursive forms, it

was hailed by many scholars as definite evidence that the modern Arabic script

had evolved from the late Nabataean script. Many prominent Muslim scholars

(who lived only a few centuries after the script’s assumed birth around the 3rd

century) believed it was derived from the Arabic Musnad script. al-Namārah inscription is also extensively cited

by historians as an important reference to the historical events of the early

decades of the prominent pre-Islamic Arab Lakhmid kingdom (al-Lakhmiyyūn)

of Hīrah, modern day Iraq. Despite more than a century since its

discovery in 1901, the reading of al-Namārah inscription is still

questionable, even at present time.

Dussaud, the French archeologist

who discovered al-Namārah stone near Damascus and transferred it to

Paris for further examination, had possibly misread the most important part of

the inscription—the first line. Based on his reading, it is generally believed

today that al-Namārah was the gravestone of king Umruʾū

al-Qays al-Bidʾ, the second king of the kingdom of al-Ḥīrah

and the most significant pre-Islamic Arab leader. Dussaud’s reading was

partially influenced by an unfortunate mistake in today’s Arabic language

grammar textbooks. To make matters worse, other scholars who read al-Namārah

in the past century uncritically strived to uphold Dussaud’s reading

fundamentals thus reinforcing its equally uncritical acceptance. To prove, at

any cost, that al-Namārah was Umruʾū al-Qays

tombstone, some were even willing to present readings that manifestly contradicted

the rules of Arabic grammar, geographical facts, and recorded history.

In order to re-read al-Namārah

inscription, I found it necessary to re-read the Umm

al-Jimāl Arabic Nabataean inscription as well since the two

inscriptions had contained identical words and shared similar historical facts

and timeframes. To read the two inscriptions, I had to also read Raqqush and

numerous other Nabataean, Palmyran, and Arabic Musnad inscriptions to study

the linguistic usage of similar words and phrases.

Regarding al-Namārah

inscription, I will, using the tools of the Arabic language, demonstrate

through in-depth analytical reading that it is not the tombstone of King Umruʾū

al-Qays bin ʿAmrū, or even about him. Written, most likely,

several years after his death, the inscription recorded the important

accomplishments of a previously unknown personality, ʿAkdī,

who was possibly one of Umruʾū al-Qays bin ʿAmrū

army generals, an Arab tribal leader who collaborated with the Romans, or

maybe a top ranking Arab soldier in the Byzantine Roman army. According to my

reading, the opening sentence was only a swearing (vow) to the soul of King Umruʾ

al-Qays bin ʿAmrū, similar to the customary opening sentence used

by Arabs and Muslims since the 7th century, Bism Allāh al-Raḥmān

al-Raḥīm بسم

الله الرحمن

الرحيم. The main

topic of the inscription was the apparent defeat of the prominent Midhḥij

tribe of southern Arabia in the hands of ʿAkdī’s fighters and

the possible subsequent control of Yemen by the Byzantine Roman Empire. The

final sentence concluded the inscription by informing the reader about ʿAkdī’’s

death, maybe in the battlefield, and stating that his parents should be happy

and proud of him. This narration is consistent with how soldiers are typically

mourned.

I am hopeful that my new readings

of al-Namārah and Umm al-Jimāl inscriptions would

prompt scholars in this field to re-examine the current readings in a

fundamentally different way. I hope that future history textbooks and the

Louvre museum will not state as certain that al-Namārah inscription

stone was the gravestone or epitaph of King Umruʾū al-Qays bin ʿAmrū.

I also hope that future publications would correct the obvious current

readings’ errors of the Umm al-Jimāl Nabataean inscription.

As a linguistic side benefit, I am optimistic that future Arabic language

grammar textbooks would cease repeating a common grammatical error regarding

simple feminine demonstrative pronouns by re-examining a poem line from Alfiyyat

Ibn Mālik. Certainly, my new readings could add even more critical,

historical, and linguistic importance to al-Namārah inscription

itself, since the language used in this inscription was clearly and

essentially classic Arabic. This can incontrovertibly prove that the grammar

and language of the Quran are deeply rooted and developed in Arabia, long

before Islam. That is, they are not Islamic or Abbasid inventions as many

Western scholars claim.

Because

a successful reading of any involved inscription, like al-Namārah,

requires a comprehensive and organized vision, I divided my reading into

convenient sections corresponding to the main topics conceived as preliminary

tools to read the full inscription. I have also provided detailed sketches and

images to guide the reader into a full visual understanding of the topic of

this particular study. Throughout this chapter, I will transliterate (following

Library of Congress rules), translate, and write in Arabic various words and

phrases to benefit the expert as well as non-expert readers.

3.2 Historical and Geographical

Overview

It is problematic to read the

inscriptions of Umm al-Jimāl and al-Namārah without

studying first the historical events taking place during the second and third

centuries CE — particularly during the early decades of the third century CE

and during the reign of King Umruʾū al-Qays bin ʿAmrū

of the city of al-Hīra,. The name of this king was mentioned in the

first line of al-Namārah inscription. Arab and Muslim historians

knew Umruʾū al-Qays bin ʿAmrū, as Umruʾū

al-Qays al-Bidʾ, meaning the first. (The desert town of al-Ḥīrah

is located less than 30 miles south of Babylon, the famed Mesopotamian city

that had fallen to the Persians over eight centuries earlier.)

Luckily, al-Namārah inscription

had provided a precise date that can easily be checked against the more

accurate dates provided by the remains left by the three main power players in

the Arabian Peninsula during that time: the Persians, the Roman Byzantines,

and the Yemenite Arabs. Several other Arab kingdoms existed too, but they were

either very weak or tightly under the control of either the Persians or the

Romans who fought for the conquest of new territories in the peninsula. After

the fall of the northern Arab Nabataean kingdom of Petra at the hands of the

Romans (105 CE), the kingdom of Yemen became the only Arab power challenging

their rule in the south. Because of repeated Roman attacks, and in order to

defend their territory, the Yemeni kings had occasionally forged close ties

with the Persians. [6][30]

According to several Muslim

scholars, ʿAmrū bin ʿUday, the father of King Umruʾū

al-Qays bin ʿAmrū, was the first king of the ethnically Yemenite

Lakhmid kingdom (later, called al-Manādhirah Kingdom by the Arabs)

to designate al-Ḥīrah as the capital city. The Ḥīrah

Kingdom became the most powerful member of a tribal alliance known as the Tannūkh

Kingdom, which was established around the 1st century CE by Mālik

bin Māhir of Yemen. The Tannūkh Kingdom controlled a vast

area extending from ʿŪmān in the south to al-Ḥīrah

and the Syrian Desert near Damascus in the north, occupying the entire west

coast of the Persian Gulf, historically known as the Gulf of Baṣrah. Islamic Arab era scholars linked the Lakhmid

and Tannūkh kingdom to the powerful Maʿad tribe of

Yemen. The three kings who ruled Tannūkh before king ʿAmrū

bin ʿUday visited Ḥīrah extensively and

regularly, but probably had their capital in Bahrain or even Yemen. Most of Ḥīrah’s

original population had eventually moved north to the Anbār area

before it was made the capital city by King ʿAmrū bin

ʿUday. [14][20]

King ʿAmrū bin ʿUday’s

father was probably a northern Arab. His mother was the sister of Judhaymah

al-Abrash who was the first king and the founder of the Tannūkh

Kingdom dynasty. He maintained close relations with the Persians and ruled

before and after the time of King Ardashīr bin Bābik (224-241

CE), the first king of the third and last Sassanid dynasty, and the son of the

Zaradust priest, Bābik, who had earlier toppled the last king of

the second Sassanid dynasty. [15]

It seems that Judhaymah al-Abrash,

a Yemenite Arab, had decided to offer his sister to a northern Arab from the Ḥīrah

area to establish closer blood relation with the northern tribes. The practice

of marrying sisters and daughters to link with other tribes is quite common

among Arab tribes. As we shall see later, both of the words Tannūkh

and Judhaymah will appear briefly in the important Arabic Nabataean

inscription, Umm al-Jimāl, found south of Damascus and believed to

be dated 250 CE. According to sources, King ʿAmrū bin ʿUday

took advantage of the temporary weakening of the Sassanid Persian Empire after

the death of King Ardashīr bin Bābik and decided to invade the

Persian-controlled Arab areas of Bilād al-‘Irāq (Mesopotamia) with

the help of the Romans and the Arab tribes north and west of Ḥīrah.

[20][30] His action had therefore reversed

the traditional alliance of the previous, purely Yemenite, kings of Tannūkh

with the Persians.

After the death of King ʿAmrū

bin ʿUday in the year 288 CE, his son, Umruʾū al-Qays

bin ʿAmrū took over and decided to expand on his father’s

attacks even further to include all Persian-controlled areas in Arabia. He was

the first Arab leader who seriously attempted to unify all parts of the Arabian

Peninsula in a single kingdom challenging both the Romans and Persians, and

was therefore considered the most revered man in Arabia before Islam. Taking

advantage of further conflicts within the Sassanid Persian royal family, he

had even crossed the Persian (Arabic) Gulf to raid the heartland of Persia.

Pre-Islamic Arabic poetry spoke of several virulent raids by the Arab tribes

against the Persians in Bilād al-‘Irāq. It is known that poems are

the most important record-keeping evidence of the Arab tribes who

traditionally relied on memory, not writing, to document their events. King Umruʾū

al-Qays succeeded in bringing most of the Arabian Peninsula under his

control except for the powerful Yemen and the Roman-controlled Arab kingdom in

Syria, known as al-Ghasāsinah Kingdom. History recorded that,

because the Roman supported the campaigns of Umruʾū al-Qays, the Persians

were forced to accept a deal with the Romans (298 CE) whereby they ceded many of

their previously captured territories in Mesopotamia.

A decade later, a new powerful king

took over Sassanid Persia. He was Shabur

II (309-379 CE) known to the Arabs under the nickname Dhū

al-Aktāf ذو

الاكتاف (the

owner of the shoulders.) It was believed that he had pierced his Arab prisoners’

shoulders to tie them together after captivity. Shabur II regained

control over most of the areas lost to the Romans and their Arab allies. It was

said that he had captured Ḥīrah, the seat of King Umruʾū

al-Qays, after a bloody battle in the year 225 CE, three years before the

date mentioned in al-Namārah inscription. [14][15] However, it is not known whether

King Umruʾū al-Qays had survived that battle. Only after the

discovery of al-Namārah and subsequent Dussaudʾs reading had

experts claimed that King Umruʾū al-Qays had escaped to

Damascus and died in the city of Bosra on December 7th, 223 Bosra

(equivalent to 228 CE), which is the date mentioned in the inscription.

I have to mention, however, that

there is no other evidence supporting the above claim except the supposed evidence

of al-Namārah inscription. Nonetheless, based on my reading

of the first line of the inscription as a vow to his soul, I am prone to think

that he died earlier, possibly in the battle of Ḥīrah, 325

CE. After the death of king Umruʾū al-Qays, the Roman and

Persians fought extensively all over Arabia until the year 363 CE when they

finally signed a treaty acknowledging Persian supremacy over Iraq. [15]

Consequent to fierce Arab attacks

on the Sassanid forces stationed in Mesopotamia (330 -370 CE), descendants of

king Umruʾū al-Qays were allowed to go back to al-Ḥīrah

and rule under the protection of the Persians. Finally, the Muslim Arabs

defeated the Persians in the battle of al-Qādisiyyah (638 CE) which

effectively put an end to the Sassanid Empire. [14][30]

In the early decades of the 4th

century CE, Yemen, the seat of the oldest known Arab kingdoms in the peninsula,

was a prime target for both the Romans and the Persians. The Yemenites were

generally referred to by the rest of the Arabs as al-Ḥimīriyyīn,

and depending on whom and when, Yemen was additionally known as Midhḥij

or Maʾad. The tribes of Midhḥij and Maʾad

are the largest and most powerful tribes in Yemen. Being the most powerful

among the Arab kingdoms of that time, Yemen had maintained its status as an

independent kingdom.

As mentioned earlier, King Umruʾū

al-Qays was never able to control Yemen. In fact, during his time around

the year 300 CE, a Yemenite king named Shammar Yuhar‘ish, was

able to unify Yemen including Haḍramawt to create a powerful

kingdom. [6] If logic matters, It would be

impossible that a defeated king Umruʾū al-Qays, who had just

lost his capital city of al-Ḥīrah in a bloody battle around

the year 225 CE, would accomplish the highest military victory of his times—

the conquest of Yemen— at the same time of al-Namārah (328 CE.)

Reportedly, king Shammar

Yuhar‘ish had maintained close relations with the Persians by sending a diplomatic mission

to the Sasanian court at Ctesiphon, al-Madāʾin, Iraq. [6] Khawārizmī, a

prominent Muslim

scholar who lived during the early Islamic centuries called him Shimr Yarʿish

or Abū Karab Bin Ifrīqis, which could mean he was of African

origins as per the use of the word Ifrīqis. No diacritic vowel was placed on the first word

shimrشمر

. This could indicate

that his name was either Shimr — a classic Arabic name—, or Shammar —

a well-known name of a prominent Arab tribe in Northern Najd. I do

believe though, it is the former because al-Namārah inscription

has one mīm letter in the name. Khawārizmī further

wrote that King Shimr was called Yarʿish (trembling) because

he was suffering of a nervous condition that made him tremble. According to Khawārizmī,

King Shimr Yarʿish was, as claimed by some, nicknamed king Dhū

al-Qirnayn (the one with two horns) contrary to the belief of many who

thought this was a nickname for the Macedonian conqueror, Alexander the Great.

Further, Khawārizmī

listed King Shimr Yarʿish as the 20th king of Yemen

before Islam and listed king Umruʾū al-Qays bin ʿAmrū

as the 21st king of al-Ḥīrah before Islam. [14] This means, the two kings had

ruled approximately during the same period.

In fact, the dates reported by Khawārizmī’s

coincide well with the dates provided by historians today. Most importantly,

this coincidence would make it highly probable that King Shimr Yarʿish

was indeed the king of Yemen during the times of al-Namārah

inscription.

While it is not impossible that

King Umruʾū al-Qays bin ʿAmrū could have died in the

year 328 CE, the historical evidence, including al-Namārah inscription,

indicates otherwise. Again, I do

believe that he died between the years 309 CE after Shabur II took

power, in 325 CE, the year al-Ḥīrah

was captured. As we shall see later, when reading al-Namārah, the

historical analysis above could become vital to the understanding of the

events, dates, and names appearing in the inscription.

3.3 Rereading the Umm al-Jimāl Nabataean Arabic Inscription

As mentioned earlier, according to Western

scholars, among the numerous Nabataean inscriptions discovered so far, only

three were written fully in the Arabic language. Dated 328 CE, al-Namārah

was the latest inscription of the three. The two earlier inscriptions are Umm

al-Jimāl, found in the same area, around Damascus, where al-Namārah

was found, and Raqqūsh, found in Madāʾin Ṣālaḥ,

not very far south of Damascus in Northern Ḥijāz. Both areas

were previously Nabataean territories. Raqqūsh indicated the date

of 267 CE while Umm al-Jimāl, which explicitly mentioned the names Judhaymah

and Tannūkh, was dated around the year 260 CE, clearly a successful

estimate when checked against our geographical and historical review in the

previous section. The two inscriptions are therefore older than al-Namārah

by at least 60 or even 70 years. This would make them useful references for

this study. As we shall see later, reading the three inscriptions together is

valuable for the separate reading of each one of them correctly.

While Raqqūsh and Umm

al-Jimāl were decidedly gravestones, al-Namārah could be

either a gravestone or an honoring monument (I shall come back to this later.)

Further, as Raqqūsh and Namārah included several text

lines, Umm al-Jimāl was brief. Unlike in Namārah Umm

al-Jimāl the language used in Raqqūsh was not classic

Arabic entirely.

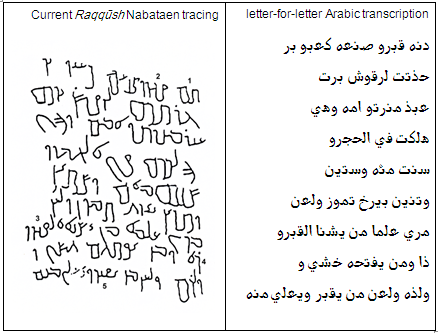

Moreover, the Nabataean script used

in both inscriptions was not solidly cursive, and did not follow closely current

Arabic cursive rules. Both inscriptions clearly started with the word dnh

دنه, but scholars

read the word differently in Raqqūsh where the first letter dāl

was slightly attached to the second letter nūn forming another

possible shape. The Arabic word qabrū (tomb) was mentioned three

times in Raqqūsh, and was read as such by all scholars. The same exact

word though in Umm al-Jimāl was read as a person’s name, Fahrū,

which clearly was an error, as I will demonstrate later. [11]

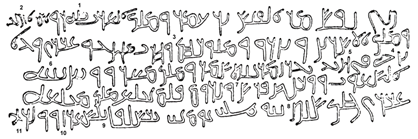

Figure

(3.1) Arabic Nabataean inscription Raqqūsh, dated 267 CE,

with author’s improved tracing. Numbers added to facilitate discussion.

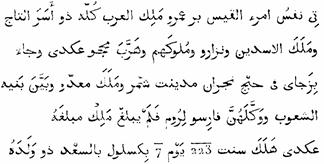

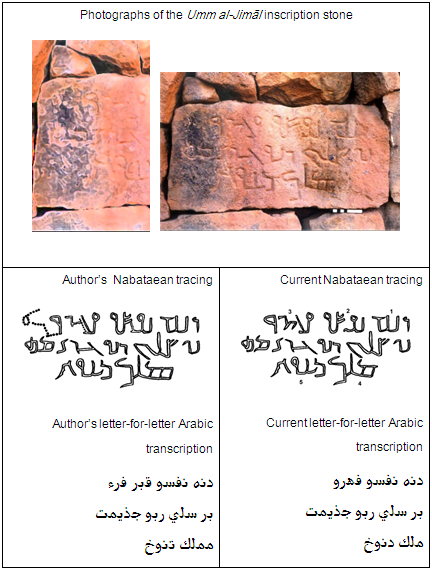

Figure

(3.2) Arabic Nabataean inscription of Umm al-Jimāl, dated

around 250 CE, with current and author’s tracing and reading for comparison.

Numbers added to facilitate discussion.

Unfortunately, I was unable to view

enough photographic details of either inscription. However, for the purpose

of this study, I feel it is adequate to rely on the available Nabataean

tracing of Raqqūsh. A word of caution: without retracing it

personally, I would be reluctant to offer a full letter-by-letter transcription

or modern Arabic reading.

As for Umm al-Jimāl,

examining a high-resolution picture of the stone was very sufficient to

illustrate the validity of my new tracings of a few key words in the

inscription. Accordingly, I provided here the above original photo and another

zoomed-in photoshoped image of the eroded re-traced area of the stone, along

with current tracing — a letter-by-letter Arabic transcription and

corresponding modern Arabic translation. Based on this new tracing, a new

detailed reading emerges that significantly differs from the current reading.

In Figure 3.1, the first word in Raqqūsh

and Umm al-Jimāl was clearly a three letter word dnh, but

scholars differed both on its tracing and reading in Raqqūsh. Some

read it as th ته, claiming it was an Arabic simple

feminine demonstrative pronoun; this is neither correct nor possible since the

following word qabr is a masculine noun. [23] Others read it as the Arabic letter

dhāl, probably for the simple masculine demonstrative dhā

ذا, which would

contradict directly with the reading of word #4 in the same inscription

showing dhā spelled as letter dāl with dot above

followed by alif. [11] Yet, few traced it as dh.n.h

for dhnah ذنه claiming this

was a northern Arabic feminine demonstrative pronoun.

However, most scholars traced word

#1 in both inscriptions as dnh, a word present in numerous other fully

Nabataean inscriptions, and read it as an assumingly Aramaic masculine

demonstrative. I traced it in both as dnh, too, but I read it as adnāh,

أدناه, a

word used in Arabic to point to a nearby object or text that is located

generally below the horizontal visual level. The beginning alif with hamzah

above was possibly omitted because the word was possibly pronounced dnāh

دناه, in

the local Arab Nabataean dialect. Raqqūsh and most other

inscriptions used several local dialect words, notably bir for bin,

or ʿabdh for ʿabd. Otherwise, beginning alif-hamzah

could have been omitted, just as the second alif between the letters nūn

and hāʾ was omitted, consistent with Arabic writing throughout

the 8th century CE, as evident in all available inscriptions and manuscripts.

The

Arabic word adnāh is utilized extensively today in the meaning of

“see by, or near, you”, “see below” or “the following below.” It can be used

effectively as a gender neutral demonstrative in the meaning of hunā

هنا as in “here”

or “here in”. When I searched for the use of this word in older Arabic

references, I was surprised that I could not find any documented evidence of

its usage in that contest. Assuming my reading is correct, which it is, this

would make the two inscriptions the earliest Arabic references documenting the

usage of the word in such manner. The word danā,

a classic Arabic verb, means “became physically close or near to someone or

some object.” [13] Among numerous examples, the Quran

(53:9) used it in ثُمَّ

دَنَا

فَتَدَلَى

فَكَانَ

قَابَ قوْسيْن

أَوْ أَدْنَى. Also, the Islamic

Ḥadīth used ʾadnāh min nafsih to describe

how Prophet Muhammad had a visiting Arab king sitting — physically — very

close to him. [17][26] Less likely, this word could be idnah

إدنه for the

imperative: “come close to,”omitting beginning alif-hamzah with kasrah.

Regardless of how one would read the first word dnh, the most important

fact is that it was explicitly used as a word pointing to a masculine object: qabr

قبر and

consistently used as an opening word for most Nabataean gravestones,

including these two.

In Umm al-Jimāl

scholars spelled the next word after dnh, as n.f.sh.ū, and

read it نفشو supposedly

from a “Semitic” feminine noun napšʾ or from Arabic nafs as

in the Quran (89:27)يَا

أَيَّتُهَا

النَّفْسُ

المُطْمَئِنّةُ . This same

word can also be pronounced in Arabic as nafas in the sense of “inhalation

or breathing” which would be a masculine noun. It is not clear, how scholars

pronounced this word found in various Nabataean inscriptions as napš or

napiš, still, in both cases it would be a feminine noun. Even before

analyzing the meaning and usage of nafsh, one can already suspect

through Umm al-Jimāl that its current reading is questionable since

the word dnh was used in Raqqūsh, and many other Nabataean

inscriptions to point to qabrū, a masculine noun. This

contradiction can only be solved by relating dnh as adnāh, a

neutral Arabic demonstrative pronoun, as I have argued above. As we shall see

later, dnh was used to point to a feminine noun, mqbrtʾ, in

at least one Nabataean inscription from Petra. Alternatively, dnh

could be pointing to a third masculine noun and the second word nafsū

is not a noun (I shall discuss this soon.)

Still, it is also possible that the word nafsū was actually naqshū

نقشُ, for the classic Arabic masculine

noun, naqsh (etching), used to indicate the act of writing or sketching on

all mediums including epitaph’s stones and even sand. [13][22] Unlike the Nabataean letter fāʾ,

which is a left starting loop with a right side downward vertical stem, the

letter qāf is a circle attached in the middle to a downward

vertical stem. This was evident in the three inscriptions.

Reading the second word (let us

call it #2) of Umm al-Jimāl as naqshū can conflict with

the current reading of word #3 of the inscription, which is thought to be Fihrū

for Fihr فهر, a classic

Arabic name. Even though it is possible to read the opening phrase (based on

our reading of the second word as naqshu) as adnāh naqshu

Fihrū bin Sāllī, after examining the photo of Figure 4.1 and

even according to the current tracing it is clear that word #3 of Umm

al-Jimāl is not Fihrū. It is qabrū, followed

by a first name containing the letters fāʾ , rāʾ and

alif/hamzah as in Faraʾ فَرء or Firāʾ

فِراء, an old

Arabic male name meaning “wild donkey” which is known for its excellent skills

to escape hunters! This name was possibly modified to Faruʾ فرُء according

to old Northern Arabic and Aramaic practice of using wāw sound at

the end of names.

In the Hadith, Prophet Muhammad

told Abū Sufyān: “You are as they say, all hunting is in the belly of the wild

donkey’”. Translated from the Arabic text: يا

أبا سفيان!

أنت كما قال

القائل : كل

الصيد في جوف

الفرإ . [13] The three partially damaged

letters for Faruʾ can

clearly be traced in the subsequent space, which is suspiciously wide for an

intentional space! To illustrate my point, I provided a partial image of the

stone utilizing the Brush Strokes filter utility in Photoshop to emphasize

stroke edges and reveal the new traced letters. The third word (we indicated

with #3) has only one prominent long horizontal stroke connected to the letter rāʾ

on the left, just as it was the case with medial letter bāʾ in

qabru of Raqqūsh (words #3, #4, and #5). There is a short

downward line pointing to the left that seems to be stone discoloration, not a

stroke. Nevertheless, even if it were a stroke, the formed shape would surely

not resemble the Nabataean letter hāʾ. A second short,

left-pointing, downward line just below the letter rāʾ is not

a stroke either, as it resembles an extensive crack. The only difference

between the word qabr we see in Umm al-Jimāl and the one in Raqqūsh

is that the upward line stroke forming the medial letter bāʾ in Umm al-Jimāl

was not vertical. Instead, it was pointing left as it was the case with the

previous word nafsū and the following word Faraʾ—

clearly a scribe hand-writting style. One can even spot another faded

parallel, left-tilted line connecting to the horizontal stroke of that letter

thus forming a classic Nabataean medial letter bāʾ, slightly

affected by a possible scriber style or error, stone discoloration and crack,

or a subsequent alteration. Moreover, the first letter of this word is clearly

qāf, not fāʾ, which can easily be compared to

the many letters qāf in al-Namārah and Raqqūsh.

Reading word #3 in Umm

al-Jimāl as qabrū or qabr would allow more

possibilities for the meaning and usage of the previous word. An alternative to

my reading of the word as naqshū, could be nafsū, but

in the meaning of nafsuhū, hūwa nafsuhū, for

“itself”, referring to qabr. This reading would fit well with reading dnh,

either as a masculine, or as a neutral demonstrative. The beginning phrase

could then be “this itself is the tomb of” similar to hadhā hūwa

qabr هذا

هو قبر, a standard usage on gravestones in Arabic, or hadhā

nafsuhū qabr هذا

نفسُهُ قبر. To

summarize, an initial modern Arabic reading of the opening phrase of Umm

al-Jimāl inscription could be either dnh naqshū qabr Faruʾ

bir Sāllī هذا نقشُ

قبر فرُء بن

سالّي, or dnh

nafshū qabr Faruʾ bir Sāllī هذا هو

قبر فرُء بن

سالّي.

However, I should now bring

attention to a curious fact: my reading of the opening phrase in Umm

al-Jimāl as nafsū qabrū or nafsū qabr is

intriguingly identical to the usual opening phrase in the Arabic Musnad

script found on eastern Arabian tombsʾ inscriptions: nafs.w.qabr نفس و قبر. King Judhaymah, whose name appears in

the Umm al-Jimāl inscription, was linked to the eastern Arabian

area where the Tannūkh kingdom was supposedly situated before

moving to al-Ḥīrah, as I indicated in my review section

above. Most scholars read that phrase as nafs wa-qabr and translated

it as “funerary monument and grave of”, by assuming that the middle wāw

was “and”. Based on this and other readings of Nabataean, Hebrew, and

Palmyra inscriptions, most scholars assumed that the word n.p.š (also

n.f.š or nafs) was used individually in the sense of “funerary monument”

or “memorial stele” (we shall discuss that in detail later.) Analyzing the Musnad

script is outside the scope of this chapter, however, the very likely meaning

of this phase should beروح

و قبر “soul and grave of.” Alternatively,

with the striking similarity between the Musnad letters fāʾ

and ʿayn, both in the Musnad Liḥyanī and Sabaʾī

styles, the word nafs could also be naʿsh نعش which

is the classic Arabic word for coffin or deathbed. It is highly unlikely that

the word nafs was commonly used among the Arabs in the meaning of “memorial

stele,” but would suddenly disappear from usage, without a trace, only a couple

of centuries later! Most important, even if the word was indeed nafs (not

nafsū) in these few Musnad inscriptions, it is extremely crucial to

observe that it was consistently used together with qabr as an opening

phrase or prologue. None of the available burial Musnad inscriptions used the

word nafs alone as a main introductory phrase preceding a name. [5][31] As mentioned earlier, based on the

Umm al-Jimāl evidence, the phrase nafs.w.qabr could have

been used to mean hadhā huwa qabr هذا هو قبر “this is the

grave of,” consistent with all other Arabic usage throughout history.

In Arabic, the three letters word nafs

is rather complex; consequently, I have some explaning to do. The root of

the word is nafas, meaning “breath” from which two main types of usage

were derived. The first includes “soul”, “life”, “person”, or “being”; the

second “self” as in “same”, “identical”, “itself”, “himself”, and “herself”. [13] This first primary usage could

even be traced to the Babylonian Epic of Gilgamesh where the god-man name Ut.napištu.m

(the Sumerian mythological prototype which inspired the story of Biblical

Noah who survived the flood) can literally be translated as “eternal great

soul-being”. Just like Arabic, Hebrew used napšā and Aramaic Syriac

used napištu. The Nabataean tomb inscriptions used l.napš.h extensively

in the meaning of “for himself”; but the words napšā

and napštā had also appeared in few other cases. [11] Palmyrenes used to portray the dead either in

relief or in statues placed on tombs. [24] They usually referred to a statue

as ṣalam (as in Arabic ṣanam). But they might have

had also referred to it — although

rarely — as napšā, or napeš

to mean “the same” or “the identical”, which 1) it conforms to the

second main usage of the word in Arabic just mentioned, and 2) it fits well

when naming a personal statue. The Nabataeans, instead, used an architectonic

form (a cone topped by inflorescence) placed on a cylindrical or square base

that they might have, arguably, referred to as napšā, or napeš,

too. These memorial stones can be carved or engraved into rock faces with an

identifying inscription that occasionally accompany them and is normally

located in the base. [24] [29]

Although unlikely, it is possible

that the Nabataeans had explicitly used the word nafash for their

architectonic-shaped personal memorial monuments, instead of their frequently

used word naṣb (as in Arabic نصب,) and for

monuments they erected for their idols. It is my firm opinion that scholars

who read Umm al-Jimāl, which was discovered after al-Namārah,

rushed to replicate, verbatim, Dussaud and other scholarsʾ readings of the

word napš to mean“memorial Monument” or “funerary Monument”.

Some even stretched its meaning to shahidat qabr, which can be

translated to “tombstone” or “burial monument”. To emphasize the usage of the

word napš, Healey referenced Le Nabatéen, by Gantineau who

defined the word as such, offering only two Nabataean inscriptions as evidence:

Umm al-Jimāl which Gantineau called the Fahrū inscription,

and al-Namārah!

In his indispensible book about Madāʾin

Ṣāliḥ tombs inscriptions, Healey further opined that this

“Pyramidal stele carved in the rock” could explain the “mysterious” absence of

inscriptions from the numerous tombs found in the city of Petra, which he

believes had banned tombs inscriptions. [10] Surprisingly though, the Umm

al-Jimāl stone and its inscription do not even conform to the physical

and inscriptional characteristics of a typical so-called Nabataean napš,

which rarely included any type of inscription except for an occasional name.

Furthermore, the majority of the hundreds of Nabataean tombs’ inscriptions

found so far had consistently used the introductory phrase dnh kaprʾ

or dnh qabrʾ. My reading of the two inscriptions listed by Healey,

in which he read the word napšʾ in the meaning of “burial monument” and the

other word, napštʾ, as “two burial monuments,” [10] led me to a different conclusion.

My initial analysis of the two

inscriptions, the Madeba and Strasbourg inscriptions revealed that the word napš

was actually used in its usual Arabic language meanings of “identical”,

“same”, “similar”, or “itself”. The opening phrase of Strasbourg inscription as

of his tracing dʾ napšʾ dy ʾabr br

mqymw dy bnh lh was possibly ذا هو نفس

الذي لأبار بن

مقيمو الذي

بناه له, or “This is

the same [tomb] that belong to ʾabār son of mqymw which

his father built for him”. The word dy is

similar to the Arabic word usage of dhī and dhū in the

meaning of “which belongs to”. [13] Also notice that dʾ (or

dā), which is spelled exactly as the classic Arabic masculine

demonstrative dhā, is unlikely a Nabataean feminine demonstrative

as believed by some scholars today. Clearly, it was used in the Nabataeean Raqqūsh

inscription (the fourth word we indicated as #4) after a masculine noun, qabrū,

not a feminine! In fact, dʾ was not used in this and several other

Nabatatean inscriptions listed by Healey as a simple demonstrative pronoun,

but as a neutral gender identity or emphasis pronoun. Very likely, its usage is

related to that of classic Arabic as in: dhā, huwa dhā or

dhā huwa as in dhātih (ذاته) ذا هو،

هو ذا for masculine, and in hiya

dhā or dhā hiyah as in dhātihā(ذاتها) ذا هي، هي ذا for feminine.

As for Madeba inscription, the

opening phrase dnh mqbrtʾ wtrty napštʾ dy ʿlʾ mnh dy

ʿbd was likelyادناه

(هذه)

هي المقبرة

والثلاثة

المشابهة لها

التي اعلى

منها التي, or

“This is the tomb, and the three identical ones that are above it, which ...” Or saying it in other words “Below is

the tomb, and the other three that look just like it that sit above it that …”

The letter tāʾ in napštʾ is likely referring to

feminine noun mqbrtʾ. The number word was possibly tlty,

from the Nabataean word for “three” tlt, not trty, which Healey

linked to tryn, supposedly a Nabataean number word meaning “two.”

Supporting this argument, the inscription listed three, not two, owners after

the opening phrase. I do believe though

that the number word tryn, for two, is actually tnyn, because all

other Nabataean number words are identical to Arabic and the Nabataean letters nūn

and raʾ can easily be mixed up. This can be verified in Raqqūsh,

where the first word of the sixth line is clearly wtnyn, not wtryn. Still, even if the number was actually “two,”

the Madeba opening sentence would beادناه

(هذه)

هي المقبرة

والاثنين

المشابهة لها

(عينُها) التي

اعلى منها التي.. or “Here below is (or this is) the

tomb and the two identical to it (that sit) above it, which…”

As a conclussion, I am convinced

that the best way to analyze the language used in any Nabataean inscription is

to rely on classic Arabic first. I see no solid evidence to presume that the

word nafsh or nafs, in an opening phrase of an Arabic or

Nabataean burial inscription, would necessarily mean “funerary monument” or

“memorial monument”. Furthermore, it is vital to observe that the word qabr

was consistently used whenever a burial place was involved, whether in Musnad,

Nabataean, or Palmyrene inscriptions. It is not impossible that the phrase nasfu

qabr could have been used to mean shāhidat qabr or “grave

marker” (stele), which may lead us to believe that the word nafs alone

could have been used to mean “marker” or shāhidah. However, in such

case, it is of paramount importance to observe that there is no solid evidence

in any Musnad or Nabataen inscription where the word nafs alone

was used to mean stele, let alone memorial monument. It is very unlikely,

therefore, that the ʾUmm al-Jimāl inscription was part of a

monument that was erected without an actual grave in a cemetery, which in turn,

is the only possible case that can justify using the word nafs, by itself,

in the meaning of “memorial monument” in an opening phrase.

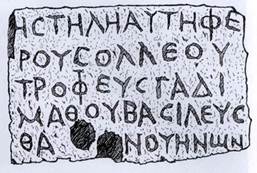

Before analyzing the final line of

the Umm al-Jimāl inscription, it is worth mentioning that although

this inscription was not a bilingual inscription, it was discovered next to a

separate stone with a Greek inscription, which appears to be an exact

translation of the Nabataean text (see Figure 3.2.) Despite my belief that the

Nabataean inscription should be the main reference to use in our ongoing

analysis (pronouncing Arabic names can be deceiving in the Greek translation),

I will analyze the first four or five words of the Greek inscription which, by

all accounts, seems to support our new reading of the Nabataean text. Although

there were no spaces in the Greek inscription, as evident in Figure 3.2, the

first five words seem are Η

CΤΗΛΗ ΑΥΤΗ

ΦΕΡΟΥ CΟΛΛΕΟΥ.

According to my reading of the Greek text, the first line can be translated in

English as “This is the stele (grave marker) of Feroo Salleoo”. Clearly, the

first name was ΦΕΡΟΥ or Feroo, not Fehroo — there is no

indication of the guttural sound of the Arabic letter hāʾ

anywhere in the word, unless the reader was invoking past Phoenician letter he

origin of the Greek Ε! My belief, the inscription used

the Greek sound OY

(sounds like oo as in wood) at the end of the first name ΦΕΡΟΥ to substitute for either Alif-Hamzah

or Dhammah-Hamzah. You may recall, according to my reading of the

Nabataean inscription, the word was either Faraʾ or Faruʾ.

The sound OY

was repeated at the end of the last name CΟΛΛΕΟΥ (Salleoo) too — in spite of the

existence of the letter Yāʾ at the end of that word in the

Nabataean text. The repeated use of the sound OY further indicates that the first name was not necessarily

ending with a wāw as experts (evidently depending mainly on the

Greek text) mistakenly assumed. I will discuss again this Aramaic and Northern

Arabic usage of the sound wāw after names, later. In addition, using the word CΤΗΛΗ (Stele) would not necessarily mean that this word was an

exact translation of nafs, because translating a text is not linear;

that is, it is not a word-for-word process. At best, this type of usage could

mean that some Nabataean Arabs used nafsu qabr combined to mean stele.

Figure

(3.3) Transcription of the he Greek Umm al-Jimāl

inscription.

More observations on the Umm

al-Jimāl inscription reading include the following:

1. Word #4 was read malk for

Arabic king. However, after careful tracing of the Nabataean text, we can clearly

see a second letter mim; therefore, the correct reading should be mmlk,

for classic Arabic mumallik مُمَلّك, which

literally means, “the one who crowned or gave kingship to”; meaning in current

context: “the founder of the dynasty of”. Moreover, reading word #4 in this way

would accurately fit the meaning conveyed by word #5 Tannūkh, king

Judhaymahʾs tribe, which, as you will see below, was inaccurately

read as Dannūkh.

2. Word #5 (Tannūkh): The first

letter of this word is clearly a Nabataean letter tāʾ, not a dāl.

As stated earlier in our history review section, King Judhaymah

al-Abrash, Umruʾū al-Qaysʾ uncle, was the

founder of the Tannūkh kingdom, or, using the inscription words, he

was the one who crowned them. This assertion can be substantiated by the fact

that Arab history never recorded the existence of a tribe or kingdom in Arabia

under the name Dannukh.

3. The final phrase would then be mumallik

Tannūkh, or “the one who started the Tannukh dynasty”.

To summarize, a leter-by-letter

transcription of Umm al-Jimāl is as follows: “dnh nfsu qbr fra

bir sali rabu jdhimat mmlik tannukh.” Line-by-line, the Arabic text is: دنه نفسو قبر

فرء - بر سلي

ربو جذيمت -

مملك تنوخ. In modern Arabic it says: أدناه

(هذا) هو قبر

فرُء بن سالّي

مُربّي جُذيمة

مؤسس مملكة

تَنّوخ, or أدناه روح وقبر

فرُء بن سالّي

مُربّي

جُذيمة مؤسس مملكة

تَنّوخ. Translated

to English, it says: “Below is (itself) the tomb of Faruʾ bin

Sālī, custodian of Judhaymah, crowner of Tannūkh,”

or “This is the soul and tomb of Faruʾ bin Sālī,

custodian of Judhaymah, crowner of Tannūkh.”

Before proceeding to the next

section, I need to elaborate on the important usage of the letter wāw

at the end of nouns. For example, notice

the words qabrū for qabr, Kaʿbū for Kaʿb,

and Ḥijrū, for Ḥijr in Raqqūsh. This

practice is consistent with that of most pre-Islamic northern Arabic inscriptions

that are available today, whether written in Nabataean or Arabic Jazm

scripts. As we shall see later, al-Namārah added wāw

after all names too. The Arabic inscriptions of al-Jazzāz (410 AD),

Sakkākah (late 4th Century), Zabad (512 AD), and Ḥarrān

(568 AD) had all added wāw after the names. This is a known Aramaic

and Northern Arabic usage which was likely incorporated into theses languages

due to Greek or Roman influence. [1][21] In fact, the use of wāw

is by itself a solid proof that most, if not all, Arab tribes which migrated

north — centuries before the Tannūkh kingdom era, especially the ancestors

of the Nabataeans — had heavily adapted the neighboring Aramaic culture. On

the other hand, classic Arabic teaches us that the wāw of ʿAmrū

is added to distinguish the Arabic name ʿAmr from ʿUmar.

My belief is that wāw originally existed in the name ʿAmrū,

and should be pronounced, at least when it is applied to ʿAmrū bin

ʿUday, father of Umruʾū al-Qays, who was likely a

northern Arab, not a Yemenite.

3.4

Arabic

Grammar Prelude: Is tī a Simple Feminine Demonstrative Pronoun?

Before reading al-Namārah,

it is important to thoroughly examine the first word of the inscription. The

word is clear and legible and has two letters: tī تي. Dussaud

claimed this word was an Arabic simple feminine demonstrative pronoun, meaning

“this is.” Throughout the 20th century, all subsequent readers of al-Namārah

agreed with him without any debate!

For example, in his comprehensive

reading of 1985, Bellamy allocated only one line to address the word where he

referred his readers to consult with two old reference books for further

explanation. [7] The first book was an enhanced

English translation of an older Arabic grammar textbook that was initially

published in 1857 in German; and the second was a British book published in

1930 and had for a subject the history of the Arabs of the western peninsula.

The author of the first book listed

among his other references, Alfiyyat Ibn Mālik, a long Arabic poem

comprising one thousand verses summarizing the grammar of the Arab language. [32]

Written by the great Arabic linguist, ʾIbn Mālik, about

eight centuries ago, the Alfiyyah is the most authoritative reference

for textbooks on modern Arabic grammar. Notably absent from his references was

an important Arabic language reference book, Lisān al-ʿArab,

written during the same period of Alfiyyah by another great Arabic

linguist, Ibn Manẓūr.

Both of these references are manuscripts that became widely available

after the emergence of Arabic typography in the 18th century.

Being a collection of poems, Alfiyyat

Ibn Mālik is only useful when read by a professional linguist. In

fact, many revered scholars, like Ibn ʿAqīl, wrote volumes of manuscripts

to explain it. Unfortunately, these scholars had to rely on a manuscript that

could have possibly included unclear words, missing verses, and scribes’

mistakes. Contemporary scholars mainly rely on these older explanations of the

manuscript, known as tafsīr. On the other hand, Lisān al-ʿArab,

predating Alfiyyat Ibn Mālik, was written with explicit explanations

by the original author along with generous examples from pre-Islamic poetry

and the Quran.

To summarize the simple

demonstrative pronouns in Arabic grammar, Ibn Mālik wrote a single

line (verse) of a poem:

|

بِذا

لِمُفْرَدٍ

مُذكَّـرٍ

أَشِـــــرْ

|

|

بِذي

وذِهْ ؟؟ تا

على الأنثى

اقتَصِرْ |

Translated into English the line

says “use dhā to point to a masculine noun, and limit yourself to dhī

and dhih ?? tā

for a feminine.” In the original

manuscript, the unclear and disputed word between dhih and tā (marked

with two question marks by the author) was either a genuine word, a corrected

word, or a crossed out word. Researching

several old tafsīr books, I discovered that scholars had read this

unclear word quite differently. [8] However, most scholars of the Islamic

Arab civilization era decided to omit this unclear word and simply list the

only three known Arabic simple demonstrative pronouns for a feminine noun: dhī,

dhih, and tā. I am listing below in Arabic a few of these

verse readings.

|

بذا

لِمفْرَدٍ مُذكّــرٍ

أشــرْ |

|

بـذي

وذِهْ تـا

على الأنـثـى

اقـتَـصِـرْ |

|

بِذا

لِمُفْرَدٍ

مُذكّــرٍ

أَشِــرْ |

|

بِذي

وذِهْ تي تا

على الأنـثى

اقـتَصِرْ |

|

بذا

لِمفْرَدٍ

مُذكّــرٍ

أشــرْ |

|

بذي وذِهْ

نسى نا على

الأنثى

اقتَصِرْ |

|

بذا

لِمفْرَدٍ

مُذكّــرٍ

أشــرْ |

|

بذي

وذِهْ

تي ته على

الأنـثى

اقـتَصِرْ |

Apparently, some overzealous and

persistent scholars decided to read this unfortunate scribe’s error by

replacing it with one or more words. Almost all of these scholars justified

their readings in Islamic religious terms. Those who claimed it was tī, explained how this reading would be

consistent with the Islamic teachings allowing four wives for one man [sic]!

With the passing of time, more Islamic scholars joined in. Some had even

claimed that Arabic has nine simple demonstrative pronouns for a feminine

noun. Some even claimed that, unlike a man, a woman does not have a specific

social status; therefore, she must be pointed to with multiple pronouns. To

conclude, unfortunately, the Arabic grammar textbook listed by Bellamy, which

most likely was Dussaudʾs main reference too, listed nine simple

demonstrative pronouns including tī, as many Arabic grammar

textbooks do today.

It is inconclusive whether the

scribe’s error in the manuscript of Alifiyyat Ibn Mālik was the

reason behind these claims. Clearly, Ibn Mālik used the word, Iqtaṣir,

which is an imperative verb meaning “limit yourself to.” My impression is that some Muslim scholars

during Ibn Mālik’s time were busy making up feminine pronouns to

support their religious claims and theories, a trend that evidently prompted Ibn

Mālik to write his grammatical poem in that strong manner to correct

them. [12] A simple online search today would

lead to more of such Muslim scholars who are overly obsessed with the topic of

females and Islam. Ironically — I must observe — to support their arguments,

some Muslim scholars desperately tried to explain that the imperative verb iqtaṣir

was referring to the masculine in the meaning of “do not use any of these

pronouns for masculine” rather than what Ibn Mālik intended the

meaning to be, which is, “use only these pronouns for feminine.”

Regrettably, I could not examine

the original manuscript of Alfiyyat Ibn Mālik. Fortunately though,

the text line being discussed is a poem text line; meaning it can easily be

checked against the well-known Arabic poetry rhyming scale Arabic typography

background with an eye to distinguish and ميزان

الشعر to determine the

correct reading. Coming from an understand Arabic letters’ shapes, and using

the simple fact that Ibn Mālik had used wāw between dhī

and dhih, I concluded that the puzzling word before tā

must be another wāw, since in Arabic, one cannot add another item

to an existing item without using wa before. It is my impression that

the scribe had simply written a badly executed letter wāw with very

small loop and long downward stroke, which can easily be confused with final yāʾ. Here is what I believe Ibn Mālik

poem line said:

|

بذا

لمُفْرَدٍ

مُذكّــرٍ

أشِــرْ |

|

بذي وذِهْ

وتا على

الأنثى

اقتَصرْ |

To test if my belief holds any

truth, I sent an enquiry to Saʿdī Yūsuf (one among the

most prominent Arab poets today whom I have the honor to know and befriend). I

included in my email five versions of the Ibn Mālik poem line,

including mine, and asked him which one would be the correct one according to

Arabic poem rhyming rules. He replied promptly, stating that the correct one

was my version, using waw before tā. I was not surprised that this would be his answer

since Ibn Manẓūr, who had studied the most important Arabic

grammar books of his time, did not list tī as a simple feminine

demonstrative pronoun in his dictionary textbook, Lisān al-ʿArab.

[13]

The second reference listed by

Bellamy for the word tī was page 152 of Ancient west Arabian,

by Chaim Rabin. [7] Rabin hinted that tī

was used as a simple feminine demonstrative noun by quoting from Bukhārī,

who wrote that prophet Muhammad had addressed ʿĀʾisha,

his youngest wife, with the phrase kaifa tīkum كيف تيكم. Rabin must

have thought that using tī in the compound demonstrative word tīkum

would mean that it was also used as an independent simple feminine

demonstrative pronoun. Writing his book three decades after the discovery of al-Namārah,

he then listed the tī of al-Namārah as second

reference! [25] Plainly said, this is wrong and

misleading. The tī of tīkum is derived from tā,

the classic simple feminine demonstrative pronoun. Ibn Manẓūr

extensively discussed this topic in his introduction to the letter tāʾ

in Lisān al-ʿArab. He explained that tā is the

simple feminine demonstrative pronoun and that it can be used as a standalone

word to point to a single feminine. He further explained: Tayyā is

the diminutive demonstrative pronoun of tā which can possibly be

used for a younger female too. Clearly, when pointing to a single feminine

noun as a third distant party, tā can be combined to form a new

compound demonstrative pronoun, as tī, but one cannot use this

part as a standalone word. For example, the words tīka, and tilka

are derived from tā, not tī. The Arabs used tīka

instead of tāka, but some had used tālika, instead of tilka,

which Ibn Manẓūr called the ugliest usage in the language. [13]. Other than this occurrence claimed

by the readers of al-Namarāh, I could not find a single example for

using tī as a simple feminine demonstrative pronoun, be that in the

Quran, Arabic poetry, or anywhere else.

Even if one were to find such an example, it would be of a wrong usage

and surely a post Islamic example. The three simple feminine demonstrative

pronouns in Arabic are tā, dhī, and dhih.

3.5

Rereading

al-Namārah Nabataean Arabic Inscription

Taking into account the numerous Musnad

Arabic inscriptions available today, al-Namārah or any of the

three other known Nabataean Arabic inscriptions cannot be classified as the

earliest Arabic language documents on record. Although the classic Arabic

language of al-Namārah is truly remarkable, the inscription

quality is not impressive. Moreover, the quality of the stone and the efforts

put to prepare it, are much higher than the quality of the inscription and the

efforts put by the scribe, and most likely, this scribe was definitely not the

same person who prepared the stone. Surely, al-Namārah stone as a

whole does not look like a stone worthy of a king’s tomb or monument. Despite

visible damages, possibly including a complete breakup of the stone into two

or more pieces, most of the words of al-Namārah inscription are uncomplicated

to read by a person familiar with the Nabataean and Arabic scripts. Out of the

several erosions that afflicted the stone, only one or two areas of erosion had

somewhat affected the reading of the inscription. Although reading al-Namārah, a

fascinating archeological and philological task, can be very challenging, it is

not very complicated once the first two lines, and particularly the first two

words, of the inscription are read correctly. Numerous scholars studied al-Namārah

after Dussaud, but Professor Bellamy of the University of Michigan should get

the highest credit for re-reading al-Namārah from scratch and

presenting original corrections along with fresh new pictures, in the eighties

of last century.

The first time I read al-Namārah

was in 2008, the year I published my first article about the history of the

Arabic Jazm script. My involvement in Arabic typography brought me earlier

into the field of history of the Arabic script. In my earlier readings, I

utilized available pictures and tracings, particularly those provided by

Bellamy. With the help of my patient brother who visited the Louvre Museum in

2009, and the aid of the great technology inside his digital camera, I was able

to examine the stone in person and obtain numerous detailed pictures of

the areas disputed by previous readers including myself. I have provided, in

Figure 4.4, the original Nabataean tracing of al-Namārah by

Dussaud, along with his initial Arabic reading as referenced today by most

textbooks. Thanks to Hassan Jamil, my ex-student and assistant who taught me

Photoshop, I was able to provide my new tracing (Figure 3.5) of al-Namārah

with eleven new changes —out of the eleven, three are Bellamy’s and six are

mine. To assist the readers locating these new tracings and compare them with

the old ones, I assigned a number to each affected area on Dussaudʾs original

tracing (Figure 3.4.) Also, in Figure 3.5, I provided my own letter-for-letter

Arabic transcription followed by my translation into Arabic of the

inscription, where I added all necessary dots, diacritic vowels, punctuations,

and missing letters alif in accordance with my new reading. I also

provided a full Arabic explanation for my readings. In addition, for those who

want to confirm the tracings of this study, I supplied a clear image of the al-Namārah

stone (Figure 3.3.)

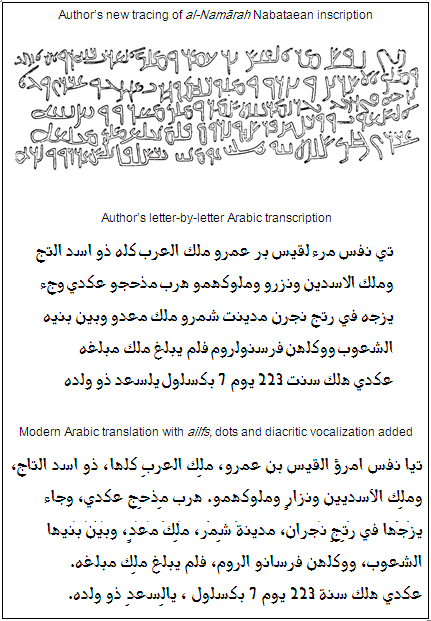

Figure

(3.4) A photo of al-Namārah stone hanging on a wall at

the Louvre Museum, Paris. © Marie-Lan Nguyen / Wikimedia Commons. [20]

|

Dussaud’s

tracing of al-Namārah Nabataean inscription

Dussaud’s

letter-by-letter Arabic transcription |

|

|

Figure

(3.5) Dussaud tracing of al-Namārah inscription with his revised

letter-for-letter Arabic transcription and

translation. [11]

Figure

(3.6) New

tracing by the author of the Nabataean text of al-Namārah

inscription with an equivalent letter-by-letter Arabic transcription and a

modern classic Arabic translation.

Line 1

Demonstrating that Dussaudʾs

reading of the first word tī was inaccurate, would most certainly

open the way to question all current readings of the inscription. After all, if

the writer of al-Namārah

inscription had wanted to use a demonstrative pronoun for a tombstone, he would have certainly used dnh,

the one utilized in Umm al-Jimāl, Raqqush, and all

other Nabataean tombstone inscriptions. Still, in order to fully accomplish

the difficult task of challenging Dussaud’s reading, we are faced by an even

more difficult task — how to read this unusual and difficult word? To begin, I

started in Aramaic where tī is thought to be a simple

demonstrative pronoun for a singular masculine noun. The name of the Syrian

village Tīshūr, Ṭarṭūs providence, is

believed to be derived from an Aramaic

compound name made of tī (this) and shūr (wall), a

masculine noun in both Aramaic and Arabic. [3][9]

However, the second word, nafs,

of al-Namārah is a feminine noun — as I have pointed out when

re-reading the Umm al-Jimāl inscription. The extremely rare

instance where nafs can be treated as a masculine noun in Arabic is not

applicable here. Considering that al-Namārah language is relatively classic Arabic, it

is seriously unlikely that it would start with an Aramaic word, let alone the wrong

Aramaic word.

Regardless of the nature of the

word nafs, feminine or masculine, one needs to first reinvestigate its

meaning and usage in al-Namārah. As stated, since this word rarely

appeared within the opening phrase of the Nabataean inscriptions but commonly

within the Musnad inscriptions of eastern Arabian tombstones (always combined

with the word qabr), scholars believe this word means “funerary monument”.

However, no other existing evidence can attest to such common usage among

Muslim Arabs. As I illustrated through my reading of the Umm al-Jimāl,

Madeba, and Stratsbourg inscriptions above, this word was likely misread or

even mistraced in these inscriptions. Among the long list of its usage in

Arabic (compiled by major Muslim scholars who lived a couple centuries after al-Namārah),

“tombstone” or “funerary monument” were both clearly absent. Two Arabic

Nabataean inscriptions, dated few decades before al-Namārah and

found in the same geographic area, and numerous other Musnad and Nabataean inscriptions,

had consistently used the word qabr in relation to a burial place. Why

would al-Namārah then use nafs alone?

Even if the word nafs was

actually used individually in few inscriptions to mean tombstone, this should

certainly not limit it to that usage or exclude others, especially since the absolute

majority of the other inscriptions had consistently used it otherwise. The fact

that Umm al-Jimāl had used nafsū with final wāw,

while al-Namārah used nafs without wāw, is by

itself a significant piece of information that needs to be examined closely.

Furthermore, al-Namārah stone does not even resemble a typical

Nabataean or non-Nabataean nafesh. I am of the opinion that in

the context of al-Namārah, the word nafs should be read as

“soul” — its common usage —, or “blood” — a less common but a very valid usage,

given the events surrounding Umruʾū al-Qays defeat. As it

will be emphasized throughout my re‑reading, the overall text contents,

paragraphs, sentences, and information on the events cited in the inscription

— whether read with classic Arabic or having Nabataean Arabic in mind — do not

match the current reading of this word as “funerary monument.”

My reading of nafs in the

meaning of “soul” would leave only a couple of possibilities for the reading of

the previous word, tī.—it was either used to swear by or call upon

the soul or blood of Umruʾū al-Qays, a very common Arab practice

even today; or to bring the attention to or call upon his glory. It was customary

that the Arabs, even before Islam, use introductory sentences before starting

with their main topic as Muslims routinely do today by starting with an attention-grabbing

swear sentence such as, Bism Allāh al-Raḥmān al-Raḥīm.

Accordingly, I believe there could be four possible readings for tī.

The first and most likely reading

of it is tayā تَيا, a combined word composed of two parts, ta and yā.

The first part is the swearing letter tāʾ, known as tāʾ

al-qasam تاء

القسم, as in ta-Allāh تَالله. Contrary to common belief today, starting with the swear

letter tāʾ was not limited to Allāh. For example,

the Arabs used ta-Ḥayātika تحياتك when swearing by someone’s life. They also used ta-rabbi al-kaʿbati تربّ

الكعبة when swearing by the god of kaʾbah in Mecca—

even before Islam. [4][13] Based on

this reading, they may have used tayā rabbi al-Kaʿbatati تيا ربّ

الكعبة. The second part, the letter/word yā is ḥarf

tanbīh حرف

تنبيه commonly used to call, or call upon, the attention of someone

or something as in yā Allāh, or yā fulān, or yā

ʿIrāq. [13] Therefore, I read the first two words of al-Namārah

as ta-yā nafs تيا

نفس, as in qasaman yā nafs

قسما يا

نفس, or bikī yā nafs

بِكِ

يا نفس, which would mean, “swear by thee Oʾsoul of”, or “in thee,

Oʾsoul of.”

The second

possible reading is that tī could also be tayā تَيا, but this time the two parts are used together as ḥarf

tanbīh. Ibn Manẓūr listed several examples where yā,

combined with additional letters before it were used as one word in the

meaning of yā. The additional letters before yā were

possibly used to add more emphasis, admiration, or to express feelings for

revenge and sorrow. The few examples listed in his Lisān al-ʿArab

included āyā آيا, ʾayāأيا , and

hayā هيا, but not tayāتيا

. [13] My

thinking, based on Ibn Manẓūr examples, is that tayā

and several other combinations of yā had existed in classic Arabic.

The third

possibility is that it could actually be tī تي, but was used either as a feminine pronoun hadhihī هذه in the meaning of ḥarf tanbīh, solely to

swear and give attention and admiration, or as a swearing letter tāʾ

with final letter yāʾ to replace the kasrah diacritic.

In the latter case, it would be read tī nafs as in bi-nafs بنفس or wa-nafs ونفس, commonly used to swear by someone’s soul. Swearing tāʾ is normally

attached to a word and used with a fathah diacritic, but it is possible

that it was given kasrah when used with a feminine noun like nafs.

This is consistent with the typical Arabic association of kasrah with

feminine. Since pronouncing ta with kasra when attached to nafs

is awkward, a final yāʾ was probably used to represent kasrah,

as practiced in pre-diacritic Arabic poetry writings.[13]

The forth,

an extremely unlikely possibility, is that tī could also be tayā,

but in the meaning of ṭawbá طوبى or taḥyā تحيا (long live.) The inscription may have started with the phrase taḥyā

nafs تحيا نفس but the ḥaʾ

after tāʾ was possibly omitted by design or by mistake. This

possibility is highly unlikely since I have not found any evidence linking tī

or tayā with such usage. Also, taḥyā is usually

used with a living person, not the soul of the dead.

Reading the

first two words of al-Namārah is crucial to the reading of the rest

of the inscription. In the case of the first three reading possibilities here

above reported, swearing by or calling upon Umruʾū al-Qaysʾ

soul, the phrase should then be followed by a single major action or event announcement,

not a group of events. As for the fourth possibility, the non-swearing

readings above, a list of accomplishments is certainly possible. Regardless of

which reading is used, the inscription has become much less likely a burial

epitaph than a memorial monument. The first three swearing readings open up

other possibilities for reading the rest of the inscription, since they

indicate that this inscription is not about Umruʾū al-Qays.

The next questionable word of the

first line was klh Dussaud traced the word as klh accurately, but

read it wrongly as kulluh. It should be kulluhā (meaning,

“all of them”) referring to the previous word al-ʿArab (the Arabs,

or the Arab tribes); both are feminine nouns. However, the next challenging

words of the inscription are dhū and the two words following it.

As I explained earlier, in Arabic dhū is usually used in the

meaning of ṣāḥib or wa-lahu (“owner of” or “he

who owns”), normally for laqab or kunyah (last name), or in the

meaning of “who or which belongs to”, or “of”. In both cases, it should be

followed by a noun. However, in classic Arabic, dhū was also used

in the meaning of alladhī (he who), followed by a verb. In al-Namārah, the next word was either asad (lion)

or asara (took someone as prisoner). I believe it was the noun asad,

and the previous word was either dhū, normally used for nicknames

or other titles, or dhū in the meaning of “who belogs to”, not alladhī.

It follows, I read the last

three-word phrase as dhū asadu al-tāj in the meaning of “the

one who owned asad al-tāj,” possibly a nickname or title referring

to a figure of lion adorning the top of an actual crown. Or in the meaning of

“the one who belongs to asadu al-tāj”. This refers to the Asad

tribe as the one with the crown or the one whose kings wore a crown, a

well-known history fact.

In order to read dhū as

alladhī, to fulfill Dussaud’s and all current readings of the

inscription, one must read the word after dhū as a verb. Scholars,

who read the word after dhū as a verb, possibly asara, assara,

or even asada, claimed that the word which followed and which can easily

be traced as the noun al-tāj (crown,) was actually referring to the

well-known historical city Thāj or Thaʾj near the

modern-day city al-Ḍahrān.

Even so, if this were true, one

would not refer to it as al-Thāj using al. In fact, Arabic

poetry had never used al with city names like Thāj or Najrān.

Additionally, in Arabic the object of the verb asar or assara must

be people, not a city. One does take people, particularly soldiers, as

prisoners and not a city! Tweaking the reading of al-tāj, some

scholars claimed it was actually al-Tājiyyīn, possibly a tribe

name, or al-Thājiyyīn, the people of the city of Thāj.

However, I was not able to trace the two or three additional letters needed for

al-tāj to become al-Tājiyyīn or al-Thājiyyīn.

Since those who read the word as the verb assara had also read each

subsequent word mlk as the verb malaka, one may ask as why al-Namārah would use assar only for al-Taj

or al-Tājiyyīn. A more pertinent question would be,

why not use malaka? It would certainly fit the meaning better.

Those who opposed reading al-tāj

as “the crown” explained that Arab kings had never wore crowns. This is erroneous.

History teaches us that some of the northern Arab kings of Ḥīrah

and even Najd, home of the Bani Asad tribes, wore crowns.

Even if this were not true, we do know that Umruʾū al-Qays had

carried many attacks in Persia whose kings did wear crowns. Since Persia

historically used a lion as a national symbol, we cannot exclude the

possibility that Umruʾū al-Qays had managed to seize a crown

with a lion effigy — this earned him the appellation: dhū asad

al-tāj (the one with the lion of the crown), a valid Arabic phrase in

terms of grammar and semantics. According to Muslim scholars, King Umruʾū

al-Qays was known for his many appellations. Doing so, that is to have

multiple nicknames, is an established Arab tradition since time immemorial, through

the Abbasid times, and even today. One would be surprised, if al-Namārah would mention king Umruʾū

al-Qays without following it with one of his many titles or appellations.

It is unfortunate that the appellation listed in al-Namārah was not among those that Muslim

historians accorded to him. [14][30]

Struggling to read the word

following dhū as a verb to prove Dussaudʾs general

classification of al-Namārah, some scholars hypothesized that assar

was an equivalent to the verb nāla (won). They read the second word

as “is”; that is, as al‑tāj (crown), and read the three-word

phrase as alladhi nāla al-tāj (he who won the crown). Yet, I

found no evidence that assara or asara was used in such manner.

Bellamy read the last four-word

phrase as wa-laqabahu dhū Asad wa-Midhḥij (and his

appellation as “the one who owned Asad and Midhḥij tribes”.)

I do agree with his tracing of the loop following Asad as possible

letter wāw, but disagree with his tracing of the word that

followed as Midhḥij. Doubly important, why would al-Namārah lists Umruʾū al-Qaysʾ

as king of Asad and vanquisher of Midhḥij in Line 2

(according to Bellamy’s reading) when his appellation already included them on

Line 1? However, I believe Bellamy’s tracing of alif as possible wāw

would change dhū asad al-tāj ذو

اسد التاج to dhū asadūl-tāj

ذو

اسدولتاج which would

conform to the way with which al-Namārah pronounced the name Umruʾū

al-Qays as Umruʾul-Qaysمرء لقيس and, as I shall

discuss later, the way it pronounced fursān al-Rūm as fursanūl-rūm

فرسانولروم. On

the other hand, even if all Bellamyʾs tracing and reading of the last

phrase of Line 1 were correct, this would still agree with my reading of dhū

as the common dhū and not alladhī, and with my reading

of the phrase as one of the king’s titles or appellations.

Reading the first two and the last

three words of the first line was, without a doubt, the most demanding task in

reading the Arabic language of al-Namārah. In comparison, reading the rest

of the inscription is straightforward. If dhū was alladhī,

one would expect a series of action (i.e. verbs) afterwards, all connected by wa (and). If it was simply the typical word dhū

for appellations, one should then expect either additional titles connected by

wa, or an announcement for an extraordinary

event or a decree. Only in the second case could one start a new sentence with

the letter wāw (not in the meaning “and”), which would normally be

followed by a non-verb, as in wa-qad, or wa-akīran. The fact

that Umruʾū al-Qays was the king of Asad and Nazār,

is neither new nor an extraordinary announcement. The Quran stated many

sentences with wāw, but it consistently used non-verb afterwards,

as in the example of Quran (53:1) wa-al-najmi

idhā hawá والنّجمِ

إِذَا هَوَى, where the word

al-najm (the star) is a noun.

In my opinion, reading the word mlk,

which appears twice in the second line, as the verb malaka is a major

mistake since the first one was preceded by the letter wāw. I read

both as the noun malik (king of), as this same word was read by all

scholars in Line 1 in the phrase malik al-‘Arab. Muslim scholars wrote

that banī Asad of Najd and banī Nazār of Ḥijāz, are ʿArabun mustaʿribah

(Arabized Arabs), not ʿArabun ʿāribah (pure Arabs.) They

are the descendants of ʿAdnān, not Qaḥṭān (presumably

a “pure” Arab.) Accordingly, ʿAdnān, a descendent of Isma‘īl, is the father (some wrote grandfather)

of Nazār of Ḥijāz and Maʿad of Yemen,

and great grandfather of Muḍar. Depending on what time period,

these mixed Arab groups were customarily referred to as Maʿad, Nazār,

or Muḍar instead of ʿAdnān. [2][28] It is evident, therefore, that after

stating that Umruʾ al-Qays was the king of all Arabs — the single

largest group of people in the area — the writer of al-Namārah needed to state that Umruʾū

al-Qays was also the king of both Asad and Nazār, two of

the largest three mixed tribes in Arabia. The third group is Maʿad

of Yemen. Yet, it is also possible that the term “all Arabs” was referring to

all nomadic Arab tribes as distinguished from tribes that had settled down in

cities and specific geographic areas and established kingdoms.

Based on my readings of the word malik

above as noun, I had suspected right from the begining, that the letter wāw

after the next word, mulūkahum, should actually be a part of that

word. This would make reading Arabic smoother, especially since the next word,

h.r.b is a definite verb, as we shall see that later. This, of course,

was not required for my reading of al-Namārah up to the word mulūkahum.

As explained above, a sentence announcing an extraordinary event, like defeating

the powerful Midhḥij, can start with wāw in the meaning

of wa-akīran (at last or finally), or hā-qad. However,

tracing and inspecting the Nabataean text, I can unmistakably see that the wāw

after mulūkahum is actually connected to it. The downward stroke of

this wāw is not vertical. It is pointing to the right. The final

letter mīm of mulūkahum has a prominent

lower-connecting stroke fading just before it reaches the downward stroke of wāw.

I read this word as mulūkahumū not mulūkahum. This

final wāw is referring to the people of Asad and Nazār.

In Arabic grammar, it is called wāw al-Ishbaʿ (saturation wāw)

or wāw al-ṣilah (relating wāw) and is usually

used after mīm al-Jamʿ (plural mīm) to emphasize

its dhammah diacritic. The word mulūkahumū is the last

word of the opening sentence of al-Namārah. It does not only conclude the

opening sentence in anticipation of the main subject of the inscription, but it

surely makes the reading of the first word of al-Namārah, tī, as “this”, impossible.

The Arabic root of the word after mulūkahumū

could either be haraba هرب (run away) or

hadhdhaba هذّب

(disciplined), a verb in both cases. Tracing this word as hrb

is accepted by all scholars. Since the word that comes after was Midhḥij,

the name of the prominent Yemenite tribe, this verb must be in past tense and

when read in Arabic must have a shaddah on the letter rāʾ

to become harraba هرّب (forced the object to run away) in order to refer to the subject committing the action of

the verb. If Midhḥij is the object, as I read it, the subject can

then be a name appearing before or after the verb. The only other possibility